Last time, we talked extensively some of the broader implications of all of this metadata stuff on the web. This time, we’re going to take a narrower focus, and look at schema.org, which is an important metadata vocabulary for the web. There is no shortage of metadata vocabularies out there, but schema.org is taking off in ways that others haven’t; the reason schema.org is spreading wildly is that Google, Yahoo, Microsoft/Bing, and Yandex (a very popular Russian search engine) are the big partners for this initiative. Whither goest Search (with a capital S), goes the web (at least, for now). Search is currently using schema.org metadata to get better rich snippets (and other services).

Schema.org provides a vocabulary to describe a wide variety of things, from Person to Waterfall. Obviously, this is intended as a generalist vocabulary for the web, but it’s constantly being extended. The variety of things that can be described is fairly broad, and there’s less specificity here than a specialized metadata vocabulary like FOAF (Friend of a Friend), or the mother of all specialized metadata vocabularies, Dublin Core. The idea is that schema.org is useful in a general web context, and is the type of thing that search engines can leverage pretty easily.

Schema.org really shines when it comes to creative works (also known as our old friend, content). There’s currently 23 more specific types of creative works (where you tend to encounter the actual thing on the web, not just a description), like Blog, or Recipe. Hmm, perhaps one could start by marking up one’s blog?

One More Time for the World: Why Metadata?

Just to back up one more step, the whole idea here with using metadata on the web is to describe content so that computers understand what that content means. While search engine technology is pretty good as figuring out relevance from complex keyword matching, computers parsing the meaning of those words is still fairly primitive. Why would we want computers to understand what our content means, if search engines can still connect our users to our content? It’s all about making smarter systems that understand the context.

For example, did you mean Houdini the escape artist, or Houdini the 1993 album by Melvins?

Context is everything, and while it’s not critical that Google knows the difference between an (awesome) historical figure and an (awesome) album, it’s great to be able to differentiate based on the context of your user, no?. Even more, in an increasingly app-ified world, mobile users are not always looking at your content in a regular web-browser, and those apps often are metadata-aware. Like, say, local concert tracking apps? There’s (more than just a bit of) metadata backing up those. Facebook loves metadata, and Twitter (astonishingly) organically got people to add metadata themselves.

Metadata is out there, and getting big. It’s highly recommended that you start thinking about how to integrate it into your content, but you will have to think a bit about some technical issues. Speaking of…

Technical Aside: Encoding Standards

One area that people often get lost with this web metadata stuff is the vocabulary versus the encoding format. For example, webmasters can implement schema.org (the vocabulary) with microdata (the encoding standard) into their HTML. Think of it like a digital audio file. The song ( the vocabulary) is the same whether it’s been encoded as an MP3 (the encoding standard) or (for the audiophiles out there) a FLAC. The digital file can be played from a computer, a phone, an iPod, or whatever else (these devices would be like HTML or XML in this increasingly stretched metaphor, and your speakers/headphones would be like the web browser).

Just as there are competing vocabularies (like Dublin Core or GoodRelations), there are competing encoding standards. Schema.org uses microdata (largely because people tend to muck it up less than other encoding formats), but there are other encoding standards, notably RDFa . I wouldn’t lose sleep over this, but if you hear about microdata (or RDFa), that’s all it is. The big takeaway is not to mix microdata and RDFa on the same page, as that will confuse a search engine.

Okay, tech aside over.

Knowledge Graph

Finally, I keep hinting at what’s going on with Google’s Knowledge Graph. To be clear, no one outside of Google knows the extent of what’s going in to the Knowledge Graph. I work at Newfangled, not Google, so this is based only on detective work, not insider secrets. Google’s not just querying some commonly available web databases like Wikipedia and scraping the info without added value. It also hasn’t created its own secret, semantically aware database of ~500 million things in the world from scratch. What we do know for sure is which companies (and communities) Google has acquired (or heavily supported) that specialize in the technologies needed to make the Knowledge Graph possible.

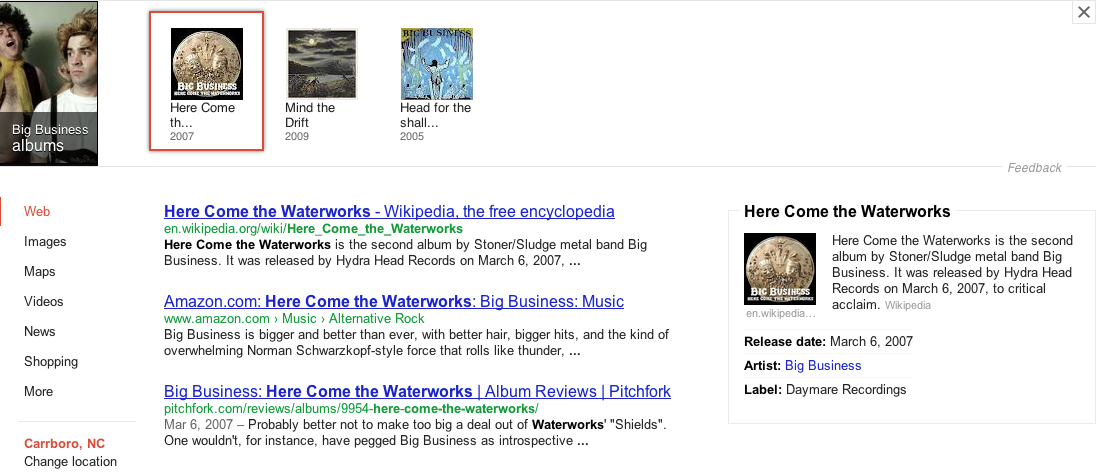

If you’re interested in what Google is doing to make these cool sidebar (and carousel) graphs, first stop is Freebase.com, which is a huge database of stuff that’s all nicely marked up with metadata. It pulls from a variety of sources, though Wikipedia is a big one. What’s going on here is that the Knowledge Graph pulls this data (and its attributions) from Freebase (and other sources of well-maintained and metadata-rich info). Freebase is like Wikipedia in the sense of being user-editable, though they’re a bit more selective about who gets the privilege to do the editing, due to the slightly technical nature of the metadata.

Anyway, Freebase contains Topics (which roughly map to articles in Wikipedia), and it has a lot of them. Many millions of topics. Music nerds take note: the music section is extremely well developed; there are over 11 million topics in Freebase’s music section, containing 38 million facts. This is one of the reasons why there are such nice rich snippets when you query Google about an album.

Google is using Freebase’s structured data (along with other databases like the CIA World Factbook), with its own info about web searching trends, statistics, and the like. There’s definitely some influence from regular, metadata-rich websites over what Google ultimately ends up showing to searchers. Also, remember that this is a very new offering from Google; as the Knowledge Graph matures, it will be looking for info from all over the web. That could mean your site, if you’re ready for it.

P.S. Google’s not the only player out there doing Web 3.0 stuff. Look at many popular mobile apps and emerging devices (that can feed into cool things like Cosm), and you’ll start to see where this semantic markup metadata structured data hashtag stuff is going.