Conversions are king

A conversion is the most valuable action a visitor of your website can do. Depending on the organization’s goals, a conversion can be a variety of actions: purchasing a product/service, filling out a call-to-action form indicating they’re interested in your services, signing up to be contacted regularly from your organization (blog, newsletter, special offers), completing a multi-step registration form, etc. All other metrics are secondary to the mighty conversion. You could pay an SEO firm to try to rank higher for particular keywords, sign up for a pay-per-click program, run advertisements through every marketing channel, but if your visitors are not becoming customers at a profitable conversion rate then you’re just wasting your money on more browse & bounce traffic.

The wrong way to improve conversion rate

In an effort to increase conversion rate, many organizations tweak the conversion points of their website based on “best practices” building on top of their current website design’s best practices, and then they hope for the best. Essentially they’re making an educated guess, hoping it works, and then — if they’re paying attention — measuring the impact compared to the month before or the same time last year. If the conversion rate goes up a bit they pat themselves on the back, and if it goes down they start wondering what they did wrong and consider reverting back to the way it used to be. These types of decisions are based on limited, inaccurate data, and even if their tweak made a positive impact, there is no way to know why it worked or if it was even the tweak itself that made the impact at all — it could just be the result of other marketing efforts, seasonality, sale pricing, etc.

The only way to scientifically improve conversion rate is to run tests on your website’s visitors

Testing the right way

Here is an example of a properly run simple test: To determine if the button color of your “Get Started Now” button makes a difference, 50% of your traffic would see the current red color (the “control” in this experiment) while the other 50% would see the new green color button (the “challenger”). Then you closely monitor the two buttons’ conversion rates, and declare a winner when you reach statistically significant results. The testing should not stop there — the followup test could pit a new challenger orange button color against the new control, or you could test new button copy: “Get Started Now” vs “Sign Up Now”

You can test any conversion point as long as it isolates a variable so you know what made the impact when the test is complete. This is why I didn’t suggest testing the red “Get Started Now” button against a green “Sign Up Now” button” — even if the challenger ends up winning, you wouldn’t know if it was the button copy or color that made the positive impact. For all you know, the copy helped and the button color hurt but overall the conversion rate was better so you might think it was right to change the color of all of your buttons. Multi-variate testing allows you to test all of the combinations of elements at the same time, which sounds superior, but if you have too many combinations the results can take a long time to materialize unless you have the heavy traffic & conversions to support this type of testing.

Testing is not for everyone

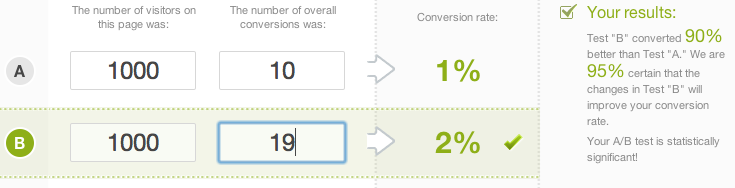

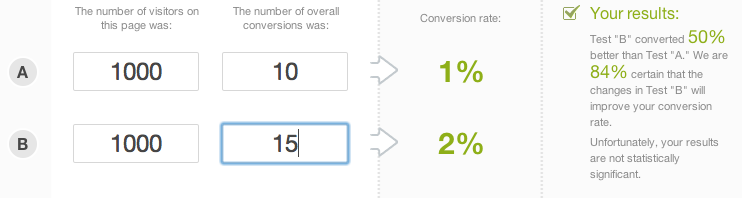

If your website doesn’t get enough traffic & conversions, even A/B tests can take a while to reach statistically significant results. Let’s say that you split 1000 visitors to the green button and 1000 visitors to the red button. The green button gets 10 orders for a 1% conversion rate and the red button gets 15 for a 1.5% conversion rate — the red button is clearly the winner, right? Not so fast. Even though the red button in this example got 50% more orders, you can only have 84% confidence in these results. Only when red button orders go up to 19 for a nearly 2% conversion rate does the calculator reach the magic 95% confidence level to deem the test results statistically significant. You don’t always have to split traffic 50/50 — only showing the challenger to 10% would minimize the risk of a big loss, but understandably it will take that much longer to reach statistically significant results.

What to test

Button color is just the easiest test to use as an example. Other testing ideas include: marketing copy, imagery, registration form flow, page layout, etc, but we don’t recommend testing these ideas at random either. Dedicated testing companies may understand everything written to this point, but by claiming that they’re somehow experts on what to test based on best practices is misleading. It’s in their best interest to have you commit to a certain number of tests in a testing program so you have a nice mix of wins & losses, but it is recommended that you generate testing ideas & priority based on usability testing. By asking people to complete a specific objective like “order an Adidas soccer ball” or showing them a particular page for 10 seconds and then asking them to tell you “What was that page trying to make you do” will reveal quite a bit about what you should test next. Ultimately your own’s site traffic will determine what works with certainty, but you should at least base your testing plan based on actual user experiences and not rely solely on the opinions & best practices of “testing experts.”

Your tests will not always win and that’s OK

Testing determines what is most effective by using your website’s own visitors, and sometimes they prefer the original even if everyone involved thinks the challenger is better. There is always something that can be learned from a failed challenger. Just imagine the negative impact if you had simply implemented the change and never tested into it. Some of the smallest tests result in the biggest gains, so don’t let the cost of testing or fear of failure get in the way of the potential ROI.