Today I had the privilege of speaking to a seminar on emerging technologies in global public health at UNC’s School of Public Health. Needless to say, public health is not exactly my area of expertise, but I was asked to focus more on how the internet and mobile devices are being used so that the graduate students attending could begin to think about how technological progress affects their work.

The event was organized by Mellanye Lackey, who had attended my talk last year on the mobile web at UNC’s Wilson Library. She initially wanted me to repeat that presentation, but after we spoke we agreed that some tweaking was in order. So, if you’re familiar with the mobile web presentation, there’s some review here (especially in the case-against-apps section) but plenty of new stuff.

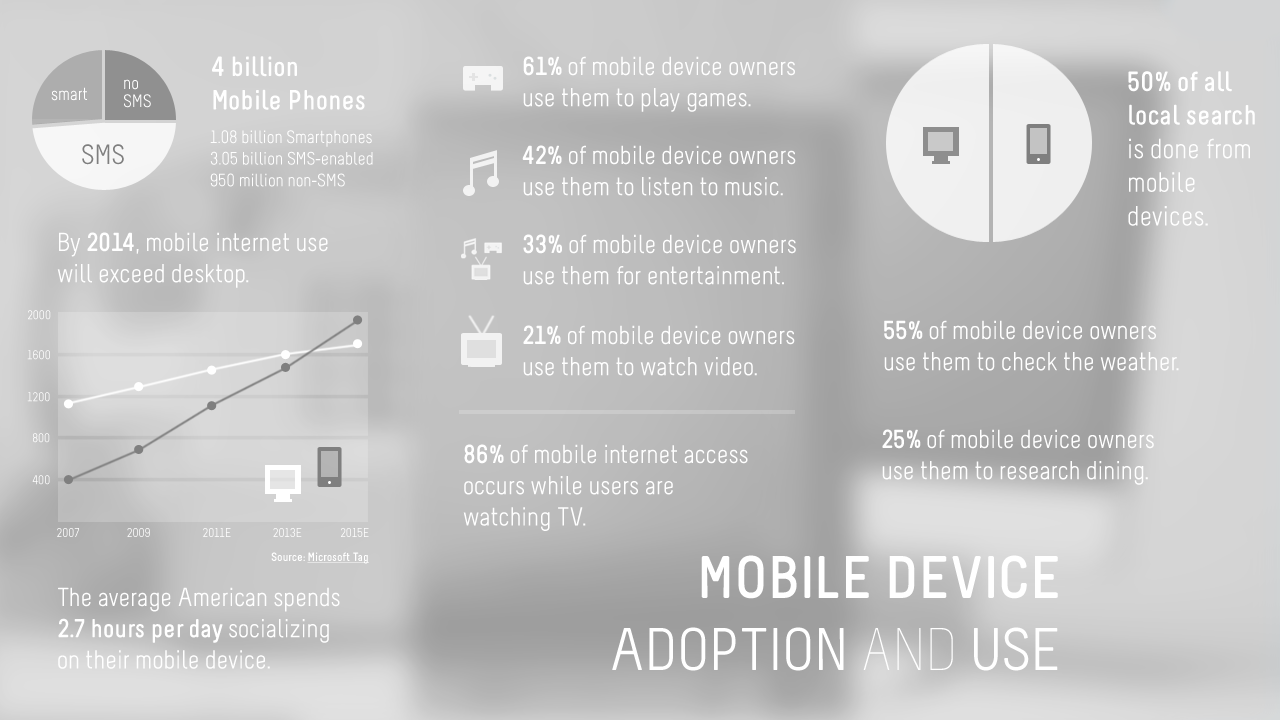

I began with the slide above (you can see the entire deck here) and asked the group if they could guess what the image was—hoping that most would assume that it was something scientific, like a microscopic biological photograph of some kind. That way, when I revealed that it was actually a typically glib marketing stock photograph, it would be a nice ice breaker. That sort of worked. The crowd of enthusiastic phone-owners is, unfortunately, typical. Not, of course, in that this is the sort of thing that real human beings do—congregate and go nuts over owning a phone—but that this is the sort of reality that clueless marketers want to portray. Unfortunately, that tends to radically skew the kinds of discussion around technological innovation toward consumerism rather than deeper issues like how technologies are used and shape human behavior. I began there because I wanted to skew the conversation back the other way. There will be a momentary interlude of marketer-friendly stats, though only to emphasize the already intuitively understood explosion of mobile technology. (In other words, unnecessary eye candy.)

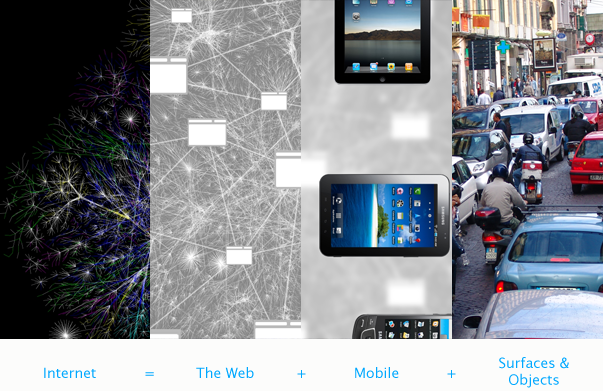

So let’s start with the internet. The internet, after all, is the foundational technology on which almost everything we do today rests. It’s also the only technology that I’m really qualified to discuss in any official capacity. (Of course, there is no internet-official credential other than using it, so I am not alone in this distinction.) But to take a step way back, it’s worth considering that we use the internet in three contexts:

- The Web — interacting with information formatted mostly by HTML and CSS and displayed on our desktop and laptop computers

- Mobile Devices — interacting with information processed by mobile applications and displayed on our smartphones and tablets

- Surfaces and Objects — expanding the sources and recipients of information to include, well, surfaces and objects (more on this later, but for the impatient, I’m basically talking about “the internet of things.”)

I will come back to the web, but I want to start with mobile devices. In fact, I’m going to focus mostly on this category. To start, it doesn’t hurt to ask what, exactly, are mobile devices? It’s not just a more complex phone. Today’s mobile devices—I’m thinking mostly of smartphones and tablets—are the first successful synthesis of three previously distinct devices that have been deeply embedded into our culture for quite a long time: They collapse the telephone, television and personal computer into one object small enough to fit into your pocket. In fact, because it is so easily carried, it has become one of our most desired, valued, and trusted objects. I’d love to see data on this, but in the absence of it, I’d bet that the average smartphone owner holds it directly in their hand for a shockingly long number of hours each day—either in use or anticipation of use—and I bet there is a substantial subset that are never outside of arm’s reach of their smartphones, even when sleeping. Each of the three previously distinct devices once received our undivided attention, but must now share it. The stats below tell this story: The smartphone is one of the most popular products of all time—powerful enough to be almost universally desired, cheap enough to be owned by a substantial global population—and it has quickly ingratiated itself to almost every aspect of our day to day lives.

Aside from texting and phone calls—the communication piece—our entertainment and productivity use of mobile devices depends largely on applications. Even though mobile devices have web browsers, the majority of mobile users prefer apps. In fact, Jakob Nielsen’s recently published a study showing that apps perform better than mobile-optimized websites. This is for a pretty obvious reason: Apps are developed specifically for the platform, whereas websites “optimized” for mobile pull double duty. In the case of monetized content, apps make financial transactions much simpler than websites, since they’re able to leverage the app store’s one-click payment functionality. Nielsen points out that the economics will continue to move in an unfavorable direction as far as apps are concerned, making development far too expensive if an app needs to be sold in the major mobile marketplaces (iOS, Android, Windows). To make matters worse, iOS alone has forked (phone/tablet), as has Android (KindleFire/everything else). This is a nightmare for developers. Nielsen says he doesn’t know when to expect a strategic shift away from apps and back to the web, but in the absence of a calendar, I’d say stick with the web now. Why? Well, let me summarize my case in three brief points…

1. Economic Oligarchy

There are currently only two major mobile app marketplaces, Apple’s and Google’s (though Windows and Amazon will begin to change that). As of January, an estimated 400,000 apps were available in the Android marketplace, and 10 billion downloads had been made since its inception (source). As of February, Apple had over 500,000 apps available and reported 18 billion downloads to date (source). These are enormous inventories. However, over half of Android’s market consists of free applications, keeping its overall revenue far under Apple’s. With only 28% of its inventory consisting of free apps, Apple is raking it in big time. In December, the value of Apple’s app store was estimated at $7.08 billion.

The average price of a mobile app in the Apple marketplace is now $3.64 (up from $1.65 last year). Apple gets 70% of each sale. With those numbers, you’d have to either be extraordinarily prolific or create an extraordinarily popular app to make any real money. Apple, on the other hand, only has to keep the shop open. This sort of situation doesn’t exactly facilitate innovation. Any developer hoping to succeed will probably tend toward emulating what’s already popular, whereas the next big thing is probably more likely to come from outside, where fewer controls exist to stifle creativity.

2. Inefficient Development

I think Jakob Nielsen said it better than I would have (or have before): Developing a decent app and making it as widely available as possible is only going to get more expensive. If each platform didn’t have its own proprietary system with unique technical requirements and approval processes, developers could focus on building something great once. Instead, they now have to focus on doing it anywhere from two to five times, depending upon how much exposure they want. This alone is a good enough reason to stick with the web, in my opinion.

3. Non-Indexable Content

Aside from the economics, this is actually my biggest complaint against apps—they’re not searchable. Unlike the web, which uses uniform resource locator character strings (URLs), there is no protocol for locating information contained within an app. Above is a great example: On the left is an article as it appears in WIRED’s iPad app. It sure looks pretty, and to be fair, there are some nice ways to navigate through the issue’s content. But there’s no way to search for it, nor is there any specific way that I can point another person to it or “bookmark” it for myself to come back to later. If I wanted to share this article with a friend, there’s no real way for me to do that. On the right is the same article on WIRED.com. With the URL at the top, I can easily come back to it or point others there. Also, I can get the same article, though with ads, at no charge, whereas the iPad version costs several dollars an issue. So why would I pay that? I’ll just leave the question hanging.

Apps have taken off despite being immediately commoditized, completely unregulated, and inefficiently organized for content.

The web, of course, offers counterpoints. First and foremost, not all information is product. If you’re going to sell content—like books, movies, TV shows, music, etc.—the app store works great. You give your payment info once, and then just about every bit of entertainment you could ever want is one click away. But that’s entertainment. There’s a ton of information that needs to be communicated, discoverable, and free. This is why academics, journalists, and civil servants are becoming more and more critical of “Big Content” and strong advocates of the web (recall the SOPA snafu). With web standards, continued development of HTML and CSS, as well as new device-agnostic approaches to development, the good old world wide web is still the best venue for the dissemination of information through the internet.

Great. So why is this relevant to public health practitioners?

Let’s start by going back to our smartphones. Aside from all this app stuff, think about what most phones can do today—not in terms of software, but hardware. With two cameras, a microphone, and GPS, smartphones are an amazing data-gathering and tracking device. Remember those scenes in old spy movies, where someone has been bugged and show up on a screen somewhere as a moving red dot over a map? Now, imagine 4 billion bugs in 4 billion pockets, sending back information about each person’s movements, and what they see and hear. Imagine what can be known about people, both individually and en masse, with the data that these tiny computers gather (assuming we don’t find ways to lie to our devices). Of course, a reasonable question is can we trust ourselves to use this information for good. More on that later.

If you’ve seen the recent Soderbergh film, Contagion, you’ll see how leveraging this technology could do much more than just find new ways to capture our attention with advertising. If you haven’t, the film tells the story of a fast-spreading virus and the CDC’s effort to track down patient zero, understand how the virus formed, and create a vaccine—all before it’s too late. The degree to which this film—as far as its depiction of the CDC and public health practitioners in general—corresponds to reality or indulges in fantasy is not something I can fully discern. But, the technology Contagion’s characters use to follow the trail of the virus—aggregating and analyzing surveillance video and data from patients’ mobile devices including call logs, text messages, and images—is within reach. My interpretation is that the film consciously utilizes a language of realism to depict something that, though a fantasy today, will be a reality soon. It’s a statement of intent—just like much of our science fiction is—to pursue that reality.

After watching this film, it occurred to me that another very recent attribute of mobile devices is the soft-AI of the automated personal assistant programs Siri and Cluzee. They’re inching toward the kind of parallel computing that any Star Trek fan has been anticipating for years: the ability to speak commands directly to a computer able to interpret the command and execute it immediately. With applications like Siri, people can at least now use mobile devices more safely—not depending upon touch and line-of-sight interactions. After all, it doesn’t appear that we’re going to get people to stop using their phones while driving, so our next best bet is to get them to stop touching and looking at them. A bit more long-term, a program like Siri could conceivably be embedded throughout a home in order to replace medical alert services of the I’ve-fallen-and-can’t-get-up variety.

Meanwhile, other technological developments will begin to extend our computing experiences beyond traditional screens. That brings us back to the surfaces and objects incantation of the internet.

There are probably going to be two stages to this transition. First, a literal extension, which will transform a variety of surfaces into screens. We first saw this several years ago with one of Microsoft’s many flops, it’s Microsoft Surface tech, otherwise known as the big-ass table. More recently, Corning has been dreaming up a glassy future appropriately called “A Day Made of Glass” in which we’ll spend almost every moment of the day moving information around from screen to screen (Part 1, Part 2). Not exactly a future I’m looking forward to, but there is an interesting sequence in Part 2 (starting at 3:07) depicting how Corning’s specialty anti-microbial scratch and chemical resistant glass could be used to distribute computing devices in health care facilities. It get’s a bit farfetched in surgery, where the doctor gets all Minority Report before projecting a hologram of a patient’s brain over his head, but the ideas aren’t bad. If you’re going to get more computing devices in hospitals, you’ve got to figure out how to do it without spreading bacteria and making people sicker. Or, get patients to do it themselves remotely, but that’s another issue entirely.

The second stage will be more figurative—an unseen result of a distributed world sensor layer that gathers vast sets of data generated by our comings and goings, pushing the boundaries of interaction far beyond the visual and quasi-tactile. IBM has been working on this for years and has created a beautiful film, THINK, demonstrating their vision. In the image above I’m showing how it might look if people, transportation devices, roads, sanitation and electrical systems were all part of an internet-connected system. I explained this in a piece I wrote recently for HOWInteractive.com on the future of interactive design. I’ll just pull from there rather than re-write it:

The good news is that we’re making amazing progress with awareness technology—and it’s not all dystopic surveillance and Skynet. Much of it has been based upon the use of radio-frequency identification, or RFID, a technology that can be minuscule and embedded into objects so software can “see” where those objects are and “feel” how they’re being used. This kind of monitoring and analysis could help us design better systems of all kinds—from “smart” buildings to more efficient roads, transit systems, electrical grids, and much more. The possibilities are very exciting.

But it’s not about building a techno-utopia. For me, a world with more machines is not necessarily a better world. The reality is the problems we face—the crumbling infrastructure, a dwindling supply of natural resources, pollution—have outscaled our cognitive capacity. We’re smart enough to recognize them, and even to propose legitimate solutions to some of them. But we’re not fast enough to get to them all before the damage is too great, and we’re not able to see how they’re interconnected to avoid proposing a solution that might nip one issue in the bud but make another worse. There’s an urgency here that’s just as significant a motivator as exploring a new technology. So, if there’s any hope of a world with a healthy balance of the natural and the technological, we’re going to need to increase the ubiquity of the machine in the short-term. Sure, it’s daunting, but what could be more inspiring than working for a better world?

Without edges, everything is vulnerable.

What do I mean by this? Well, I imagine that after taking in all of this information, anyone might feel pretty nervous. After all, I’m describing a world in which much more data about you is available than ever before, and to more people than ever before. For example, plenty of companies today are selling single-sign on systems to hospitals that offer significant value in terms of procedural efficiency gains. If a doctor can sign in system-wide once using a biometric of some kind (fingerprint or retinal scan, for example), she might save a significant amount of time in the aggregate—time she can instead spend treating patients. But this also means that a third party now has access to a significant amount of the hospital’s data. With enough customers, a third party single-sign on software company could be vulnerable to hackers, putting a tremendous amount of patient data at risk. For this, there are solutions, of course—things like firewalls and encryption. But the point is that as the complexity of our data collection and analysis practices grows, the need for security and privacy measures compounds. No system will ever be 100% secure.

Additionally, there are legal compliance issues to navigate that pertain to patient information confidentiality and security requirements for technological systems that interact with that information. Instead of developers being expected to gain expertise in things like HIPAA compliance (familiarity, yes; expertise, no) those involved in healthcare of any kind should grow in their understanding of technological issues. Each side needs to bring awareness and a point of view to the table and cooperate in order to ensure the best result. I only mention this because I’ve observed the opposite.

But that’s not really where the discomfort ends, unfortunately. IBM noted in their THINK exhibit that traffic pattern analysis was not only beneficial to improving city planning, but in developing predictive algorithmic engines for driver behavior. In other words, research is beginning to show that what you do behind the wheel can be predicted. And you thought you were in control, did you?! With a worldwide sensor layer like the one I described, we can only imagine the insights that will be gained by analyzing the resulting data. The benefits of constructing this layer, in terms of solving those big, worldwide problems, may be well worth the privacy and individuality sacrifices, but we need to make that decision intentionally. It’s worth pointing out that in Contagion, every bit of information the CDC was able to analyze was gathered as a result of the characters’ willing forfeiture of privacy—by using cellphones, the internet, being in public places, and using public transportation. Just like we do. We are already building this sensor layer. What is likely to make us uncomfortable even just in anticipation of a broader system like the one I described is the notion that our patterns could be so easily predicted, as IBM expects. This will call in to question not only our individuality, but our agency.

This kind of philosophical question is beyond the scope of this post, but I want to leave it with you to think over. Technology is also like a mirror, and if it begins to reflect back to us something that we don’t recognize, we must determine why and what, if anything, we can do about it. We need to be comfortable pushing any technological discourse—no matter how low-level, like the apps-vs-web debate—into this territory in order to ensure that we never lose sight of the big picture, which is ultimately a balance between two questions: What kind of a world do we want to live in? and What kind of a world do we live in?