My second Interaction column for Print Magazine is now out in the August issue! (June issue column here.) My original title was “Post-Desk Content,” but the editors reframed it as an interesting question: “How Should We Contain the Cloud?”

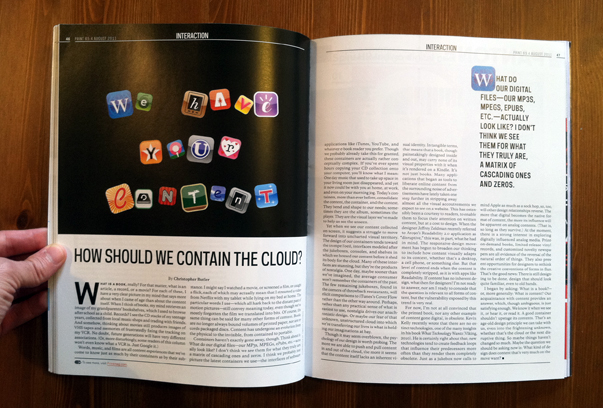

I’ve reposted it here, though you can read it over at Print, or, for the best possible experience, pick it up in its native yet ephemeral dead-tree format 😉 The illustration was created by Timothy Goodman, who has lots of other good work on his site.

What is a book, really? For that matter, what is an article, a record, or a movie? For each of these, I have a very clear picture in my mind that says more about when I came of age than about the content itself. When I think of books, my mind retrieves an image of my grandparents’ bookshelves, which I used to browse after school as a child. Records? I see the CD stacks of my teenage years, collected from local music shops and trading with friends. And somehow, thinking about movies still produces images of VHS tapes and memories of frustratedly fixing the tracking on my VCR. No doubt, future generations will have very different associations. (Or, more disturbingly, some readers of this column won’t even know what a VCR is. Just Google it.)

Words, music, and films are all content experiences that we’ve come to know just as much by their containers as by their substance. I might say I watched a movie, or screened a film, or caught a flick, each of which may actually mean that I streamed a video from Netflix with my tablet while laying on my bed at home. The particular words I use—which all harken back to the distant past of motion pictures—still convey meaning today, even though we’ve mostly forgotten the film we translated into bits. Of course, the same thing could be said for many other forms of content. Books are no longer always bound volumes of printed paper, nor are records packaged discs. Content has undergone an evolution from the physical to the invisible, from contained to portable.

Containers haven’t exactly gone away, though. Think about it: What do our digital files—our MP3s, MPEGs, ePubs, etc.—actually look like? I don’t think we see them for what they truly are, a matrix of cascading ones and zeros. I think we probably just picture the latest containers we use—the interfaces of software applications like iTunes, YouTube, and whatever e-book reader you prefer. Though we probably already take this for granted, these containers are actually rather conceptually complex. If you’ve ever spent hours copying your CD collection onto your computer, you’ll know what I mean: One day music that used to take up space in your living room just disappeared, and yet it could be with you at home, at work, and even on your morning jog. Today’s containers, more than ever before, consolidate the content, the container, and the context. They bend and shape to our needs; sometimes they are the album, sometimes the player. They are the visual layer we’ve made to help us see the unseen.

Yet when we see our content collected on-screen, it suggests a struggle to move forward into uncharted visual territory. The design of our containers tends toward the trompe l’oeil, interfaces modeled after the jukeboxes, consoles, and shelves in which we housed our content before it shed its body for the cloud. Many of these interfaces are stunning, but they’re the products of nostalgia. One day, maybe sooner than we’ve imagined, the average consumer won’t remember the containers of the past. The few remaining jukeboxes, found in the corners of throwback restaurants, will elicit comparisons to iTunes’s cover flow rather than the other way around. Perhaps, rather than any practical sense of what is easiest to use, nostalgia drives our anachronistic design. Or maybe our fear of that unknown, unstructured cloud into which we’re transferring our lives is what is holding our imaginations at bay.

Though it may seem overblown, the psychology of our design is worth probing. The more we are able to push and pull content in and out of the cloud, the more it seems that the content itself lacks an inherent visual identity. In tangible terms, that means that a book, though painstakingly designed inside and out, may carry none of its visual properties with it when it’s rendered on a Kindle. It’s not just books. Many applications that began as tools to liberate online content from the surrounding noise of advertisements have lately taken one step further in stripping away almost all the visual accoutrements we expect to see on a website. This has ostensibly been a courtesy to readers—to enable them to focus their attention on written content—but at a cost to design. When the designer Jeffrey Zeldman recently referred to Arc90’s Readability 2.0 application as “disruptive,” this was, in part, what he had in mind. The responsive-design movement has begun to broaden our thinking to include how content visually adapts to its context, whether that’s a desktop, a cell phone, or something else. But that level of control ends when the content is completely stripped, as it is with apps like Readability. If content has no inherent design, what then for designers? I’m not ready to answer, nor am I ready to concede that the question is relevant to all forms of content, but the vulnerability exposed by this trend is very real.

For now, I’m not at all convinced that the printed book, nor any other example of content gone digital, is obsolete. Kevin Kelly recently wrote that there are no extinct technologies, one of the many insights in his book What Technology Wants (Viking, 2010). He is certainly right about that; new technologies tend to create feedback loops that influence their predecessors more often than they render them completely obsolete. Just as a jukebox now calls to mind Apple as much as a sock hop, so, too, will other design relationships reverse. The more that digital becomes the native format of content, the more its influence will be apparent on analog contents. (That is, so long as they survive.) At the moment, there is a strong interest in exploring digitally influenced analog media. Print-on-demand books, limited-release vinyl records, and customized novelty newspapers are all evidence of the reversal of the natural order of things. They also present opportunities for designers to rethink the creative conventions of forms in flux. That’s the good news: There is still designing to be done, design that should look quite familiar, even to old hands.

I began by asking: What is a book?—or, more generally: What is content? Our acquaintance with content provides an answer, which though ambiguous, is just satisfying enough. We know it when we see it, or hear it, or read it. A good container shouldn’t upstage its contents. That’s an age-old design principle we can take with us, even into the frightening unknown, whether that’s the cloud or the next disruptive thing. So maybe things haven’t changed so much. Maybe the question we should be asking now is: What kind of design does content that’s very much on the move want?