Back in May, I wrote a newsletter on measurement with the goal of going back to the basics in order to properly understand the foundational web metrics and make sure we’re measuring what really matters. If you haven’t read that yet but are interested in web analytics, I recommend taking some time to sit down and give it some attention (it’s only two pages). In it, I focus mostly on the process of gathering data, understanding bounce rate, and measuring the value of referrals. A few comments that I received after I published the article clued me in to something: we’re still not getting bounce rate.

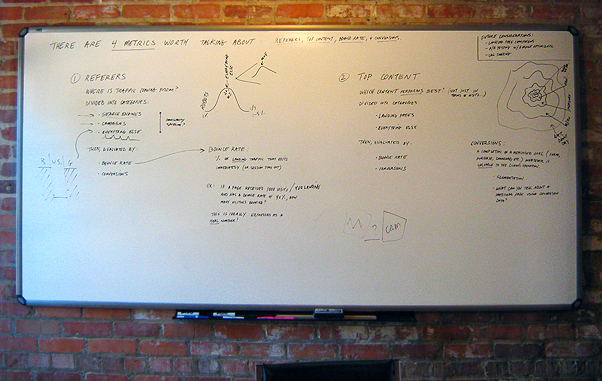

So, last week, we gathered as a team to do an internal recap on measurement—we call these “enrichment sessions” (evidence above). I want to share some basic points from that session with you, but mainly driven by an underlying message that, depending upon the type of business you run and your particular web content strategy, bounce rate may not matter as much as you think. I’ll get to that in a moment…

First, here are some general points. (I think they’re pretty consistent with our corpus on measurement, though this is a developing “field” with all sorts of moving parts—so thinking around it is bound to change as the technology changes.)

- There are 4 metrics worth focusing on:

Referrers and Top Content, understood in light of Bounce Rate and Conversions. - Referrers

Referrers should be divided into three basic categories: (1) Search Engines, (2) Campaigns, and (3) Everything Else.

Then, referrers should be evaluated by bounce rate—the percentage of landing traffic that exits immediately (or times out) and conversions—those sessions which complete a pre-defined goal (filling out a form, signing up for something, downloading an asset, etc.) - Top Content

Don’t evaluate pages in terms of isolated metrics, but ask yourself which content performs best? This might be a long-term question, as a page’s value may be seen in terms of small but consistent contributions rather than isolated spikes of activity.

Top Content should be divided into two basic categories: (1) Landing Pages, and (2) Everything Else.

Then, just like with referrers, evaluate by bounce rate and conversions.

Ok, that’s my basic framework. A bit more about bounce rate…

First, here’s what I wrote in my last article on measurement. This is really important to get:

The bounce rate measures the percentage of visitors to a web page that leave it without following links to any other pages on the site. This means that a bounce can be registered if a user remains idle on a page long enough for his or her session to be terminated (30 minutes or more), or if they click a link to a different URL that is not configured to open in a new window, or if they close the browser window outright. But the most important principle to remember is this: the bounce rate only applies to traffic that landed on a page. This means that in order to determine the exact number of bounces from a particular page, you must combine data from two different reports in Google Analytics—the Top Content Report (or Content Detail Report) and the Top Landing Pages report.

Google Analytics’ Top Content and Content Detail reports list the bounce rate along with the total number of unique visits but exclude landing data, creating the false impression that the bounce rate should be applied to the total number of visits. However, the bounce rate should only be applied to the number of visitors that landed on the page—often a much lower number than the total visits, which means that the bounce rate is likely lower than you might initially conclude.

So, two immediate takeaways: (1) You can’t expect to just glance at preconfigured reports in Google Analytics and get the full story. (2) The sitewide average bounce rate carries a very different meaning than the bounce rate of a specific page. If you have a very large site, your sitewide bounce rate is likely to be higher than the Google recommendation of 40%, and that might be ok.

Just to drive this home more fully, I wanted to include a comment string from that last measurement article, as I think it helps to clarify some points around bounce rate. I really encourage you to read through them so that the next time you dive into your analytics data, you’re asking the right questions. Here we go:

Ed: The rate doesn’t ever change, it’s a percentage, so it’s always going to be that percentage. Google’s conversion university people say that a bounce rate over 40% is problemmatic, probably why they put that metric front and center, right? It doesn’t really matter how many people come to the page. If 40% of them are leaving, that’s a problem. I like the analysis, but aren’t you just creating a handicap?

Chris Butler: What I probably should have written is that the number of bounces is likely lower than you might initially conclude by seeing the percentage displayed next to the total number of visits. This is an important fact. Let’s say the bounce rate is 50% for a page that received 2000 total unique visits. You would be wrong to conclude that 1000 visitors bounced. You would need to look at the landing page report to see how many visitors during the same time frame came in to your website by landing on that page. That is a different number, which will be less than the total number of visits. Let’s say, again, hypothetically, that the number of landings was 300. This means that the number of bounces was actually 150, not 1000. A massive difference! That is my point.

So, no, I’m not trying to prescribe a handicap. In my opinion, bounce rate is only relevant when translated to a real number of visitors. Aiming for a percentage, like 40%, simply because other people say it’s a good number is mistaken. There are too many different kinds of websites—of vastly different sizes—for that to be a realistic goal. A site like ours receives far too much traffic to a much-too-large number of unique pages for a site-wide bounce rate of 40% to be realistic. In fact, I might argue that the more content you create, no matter how focused you believe that content to be, the higher the site-wide bounce rate. There’s far too much search engine traffic across the web for that not to be true. But we can debate that point…

In any case, you ended by saying that “it doesn’t really matter how many people come to the page.” I completely disagree. Concrete numbers do matter. Percentages don’t. I want to know which visitors bounce and which convert, so the hard numbers matter. Looking simply at a percentage and saying, well, it’s higher than 40%, therefore it’s bad, is exactly the kind of “measurement” that I’m trying to steer our clients away from by writing this article. “

Alexandra: @Ed, @Chris, @Jesse, I think one area of confusion with the whole bounce rate thread is that sitewide site bounce rate and individual page bounce rate are two very different things. (I’m linking to a marketing jive post that I found helpful), but for a smaller site like mine, my overall bounce rate matters more. For a larger site like this one, it’s gonna be be higher because the overall rate is just an average of all the other pages’ bounce rates.

The marketing jive post points out that a page’s bounce rate is good or bad in terms of what the page’s purpose is. A campaign landing page with a bounce rate over 35% is probably not good, but a blog post or something with the same rate would be doing just fine.

But the big point is you can’t just look for a number and say good or bad. Page performance scales aren’t binary systems, like on or off, 1 or 0. There has to be a deeper kind of thinking here, otherwise we’re doing the same thing as teaching to the test.

Chris Butler: Yes, the distinction you raise is critical. For the most part, I’m talking about page-specific bounce rate in this article. Site-wide bounce rate, especially for a larger site with a widespread audience, is likely to be higher than 35-40%.