Today I gave a talk sponsored by the Carolina Adobe User Group at the University of North Carolina on technosprawl. I called it Human Progress Landscape. Extensive recap below.

When I was a senior in college — almost a decade ago now — I made a film called Human Progress Landscape. It was an experiment, really, in which I was asking why human progress tended to produce an environment that seemed less and less suited to humans. I didn’t come to a conclusion. I still haven’t. But the question remains important to me. What is the landscape of human progress? The interesting thing — to me, anyway — is that I made the film from the point of view of the machines. At the time, that was very much a science-fictional idea. Today, however, that is no longer so. The idea of a robot-readable world has become an accepted reaction to everyday technologies, and, as far as I can tell, not nearly as unsettling a concept as it once would have been.

A still from Human Progress Landscape, 2002.

Back then, I was thinking a little bit about the virtual landscape — the space we occupy online — but we’ve since increased the time we spend in this space considerably. It’s gotten to the point that when I think about our human-progress-landscape, I have that virtual space in mind almost entirely. But that, too, needs to change. Because while we’ve been doing some impressive digital world-building, our real world has been neglected. It’s worth remembering that without a real world, there’s little hope of sustaining a virtual one.

The future rests upon a merging of worlds.

We’ve ended up with this imbalance largely due to our preferences. Though individually, we may bristle at the notion that we are thoroughly capitalistically indoctrinated, the last 20 years or so speak for themselves. The image below is characteristic of that focus — one that skews the conversation around technology toward consumerism. It would be easy to mock the mania displayed on some of these faces, but any Google search for “line at Apple store” reveals the truth on the ground. We are dedicated to the consumer experience of technology. When the corporations build it, we bring our wallets.

We should make an effort to extend the technology conversation beyond consumerism.

But technology is obviously more than that. It’s deeper. It shapes human experience and behavior with a much broader spectrum than that narrow corridor of desire and avarice. Technology is silverware to satellites, and everything in between. Computing devices are just a tiny portion of that everything, but we’re going to see a rapid, exponential increase in them in the coming years.

More on that in a moment…

First, let’s take a closer look at the computing devices in our pockets. What are they?

In 30 years, we’ve seen an exponential increase in power and an exponential decrease in size.

One perspective is that they are the result of years of progress in processing speed, efficiency, and miniaturization. When I was only 1 year old, IBM introduced its first PC, the IBM 5150, which used a 4.77 MHz CPU and had 16 kb of RAM. Today’s iPhone has a 1GHz CPU and 512 MB of RAM. That’s an almost 4,000-fold increase in processing power and an over 30,000-fold increase in memory. Huge! Also consider that the IBM 5150 cost anywhere from $1500 to $4500 depending upon add-ons and would have been the spatial equivalent of plunking a mini-fridge on your desk. For $199 (a 96% decrease in price) you can put something thousands of times more powerful in your pocket.

But you already know this.

The smartphone is the first successful synthesis of three previously distinct machines.

Another is to think about what we do with them. From this perspective, I think of them as trifocal devices — the first successful synthesis of three previously distinct machines: the telephone, the television, and the personal computer. It’s really no surprise that the processing power made possible by the machine progress we’ve seen over the last 30 years would produce a device capable of handling all of our communication, entertainment, and productivity. But what remains to be fully understood is what happens to society — what happens to us — when phone calls don’t have to happen at home, at desks, or in booths; when we can watch TV shows and movies whenever and wherever, not just in our living rooms or theaters; when productivity is a steady stream in our waking life, not just a nine-to-five thing. We already take all of this for granted, of course. If we didn’t, it wouldn’t have sounded naive for me to say, “what remains to be fully understood.” But that’s true. Until the generation of human beings born into this paradigm shift complete a life-cycle, I don’t think we’ll really have the ability to understand the impact, and by then, there will be new factors to consider.

Meanwhile, we are going deeper. Phone calls, for example, are almost anachronistic in a world in which text messaging and social networks create an ambient awareness that has redefined what it means to be “with” someone. You can be on a bus full of strangers, yet immersed in a group chat with friends in all different places.

Technology bends time and space.

But you already know this, too.

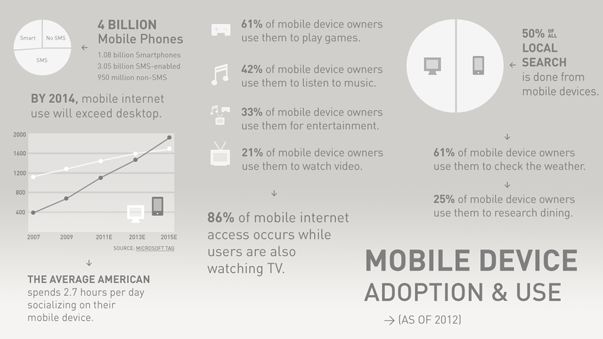

A larger version of this slide can be viewed here.

I won’t bore you with the usual litany of statistics. If you want them, you can inspect the image above later. Yes, mobile devices will outsell traditional PCs very soon. Yes, more people are connected to the internet with mobile devices than with traditional PCs across the globe. Yes, the number of mobile subscribers is roughly 5 Billion and the number of persons living on planet Earth today is 6.8 Billion. It’s all amazing.

My question is what is all of this accomplishing? For one thing, as William Powers pointed out in his book, Hamlet’s Blackberry, more work:

“However, there’s a big asterisk to life in this amazing place. We’ve been doing our best to ignore it, but it won’t go away. It comes down to this: We’re all busier. Much, much busier. It’s a lot of work managing all this connectedness… Much of what used to be called free time has been colonized by our myriad connective obligations, and so is no longer free.”

Is that good enough? I grew up watching The Jetsons, which depicted a future in which people did far less work thanks to technology. Most of that work, of course, was trivial and not worthy of the room-sized machines, conveyor belts, and robots that Hanna-Barbera drew into the Jetsons’ household. But still, the vision was one in which the technology did the work that humans used to do.

Where is our less-busy future?

Contemporary futurism (of the corporate variety, especially) has an even more limited and disappointing vision. Instead of imagining technology that will do more for us, they have us doing more for technology—namely, of the screen-based, all-day-information-management kind. See Corning’s A Day Made of Glass concept videos, as well as Microsoft’s Productivity Future Vision. Microsoft and friends are only now catching up with Minority Report, which dreamed up all the fancy screen stuff over a decade ago. Really very little “imagining” going on, if you ask me. (I will come back to Minority Report.)

Corning’s Day Made of Glass (above) is just that — screens from sunup to sundown.

Microsoft’s Future Productivity Vision (below) is a future of more screen busyness, not progress.

But here’s the point: We should be asking, what is the benefit of technological progress if it creates more trivial labor and less meaningful production for the average person?

What’s keeping us from making real progress?

One answer is wealth. The devices in our pockets represent a massive—though not evenly distributed—economy, as they are. In Africa, mobile devices have opened economic doors, that’s for sure. But in the Western world, we’re not turning mobile computing into the same kind of populist economic opportunity.

The mobile economy is dominated by Apple, which according to the most recent estimates, has control of half of the entire smartphone market. That, by the way, is a measure of number of devices. But when it comes to profit, Apple’s dominance is much more clear. According to Asymco’s analysis, Apple raked in 73% of mobile phone profits this quarter, Samsung, had 26%, HTC barely broke even, and the rest — RIM, Nokia, Sony, Motorola, LG — lost money. Why is Apple killing it? One, their devices are excellent, two, they have the App Store.

Apple’s app marketplace is the clear financial winner.

There are really only two major mobile app marketplaces, Apple’s and Google’s (though Windows and Amazon will begin to change that, and so will Salesforce, depending upon what we mean when we say “app”). At last count, the Android marketplace had 350,000 apps and had seen 10 Billion total downloads, whereas Apple’s marketplace had over 500,000 apps and 18 Billion downloads. Lots of inventory, for sure, though since over 50% of Android’s inventory consists of free applications, its overall revenue remains far under Apple’s. With only 28% of its apps going for free, Apple is just simply making more money. The overall value of Apple’s app store has been estimated at $7.08 billion. Meanwhile, Apple has over $110 Billion in cash reserves.

The average price of a mobile app in the Apple marketplace is now $3.64 (up from $1.65 last year). Apple gets 30% of each sale. With those numbers, you’d have to either be extraordinarily prolific or create an extraordinarily popular app to make any real money. Apple, on the other hand, only has to keep the shop open. This sort of situation doesn’t exactly facilitate innovation. Any developer hoping to succeed will probably tend toward emulating what’s already popular, whereas the next big thing is probably more likely to come from outside, where fewer controls exist to stifle creativity. In fact, a recent survey showed that the majority of app developers are moonlighting: 41% are full-time software developers who develop apps in their spare time, 26% are full-time mobile app developers, and 11% are students and recent graduates working part-time.

In short, wealth is being generated and consolidated by mobile technology. But as far as progress is concerned, I’m not seeing much here, nor much potential for it.

Not all information is product. Learn it!

After all, apps may be great for transactional content experiences and will be even greater for point-of-sale transactions, but they are not an adequate replacement for the kind of progress that the web has offered. Why? Because, not all information is product!

Why are academics, journalists, and civil servants critical of the nationwide focus on “big content,” app monopolies, and locked down devices? Why are they the most active advocates of the web? Because they believe that not all information is product. With HTML5, CSS3, responsive design techniques, and search engines, the web can support rich, discoverable, and sharable information experiences in any context with all the whiz-bang you need. Yet, apps are “where it’s at.” This is a disappointment that merits lots of attention. Unfortunately attention isn’t something we have in great supply anymore. If we’re putting our money where are minds are, most of our attention is being frittered away on apps.

And, you know what? Even publishers are starting to wake up to this. Here’s an enlightening piece from Jason Pontin, Editor-in-Chief and Publisher of Technology Review, on why publishers don’t like apps. The sooner we stop trying to shoehorn content that is much more at home on the web into apps, the better.

The web is better at scaleable, shareable and searchable information.

You may not have known all of this detail, but the general message isn’t really news, is it?

And why is all of this critique necessary, anyway?

Well, here’s something you may not have considered yet: Our smartphones are capable of much more than entertainment and distraction. Aside from my historical tech spec comparison, I’ve been focusing entirely on their software so far. But it’s their hardware that’s really interesting. Most smartphones have 2 cameras, a microphone (some with sophisticated voice recognition) and GPS. In other words, the most scalable, distributed, and flexible surveillance system ever built. Five billion bugs in five billion pockets across the planet. Something of this magnitude could be used for good — as realistically depicted in the recent film, Contagion — or for evil. I suppose our judgment on that will have to do with whether we trust the manufacturers, carriers, ISPs, and governments.

We should be giving that extensive thought.

The mobile network is the most scalable, distributed and flexible surveillance system ever built.

But with the addition of networked objects, this layer will become much more complex.

Earlier, I mentioned that we’ll see a significant increase in computing devices in the near future. Part of this has to do with devices like smartphones. The smartphone layer gathers data on who we are, where we are, and what we are doing, almost without interruption (how often do you turn your smartphone off?). In this way, the distributed technological layer created by those billions of smartphones is the model for our next stage of progress, which extends that layer over objects. This is what is commonly called “the internet of things.”

We’ll have “smart” appliances that regulate their own energy use, learn your preferences, and report usage data back to their manufacturers. We’ll have smart energy grids in homes, buildings, and communities that regulate energy use in clusters from a variety of sources and sell the surplus back. We’ll have roads that will report on their own structural integrity, request maintenance, coordinate road work, and even tell us all kinds of things about traffic patterns. All of these ideas fall under the umbrella of what’s called the sentient city — a city programmed for self-regulation and efficiency. It may sound like science fiction, but it’s very real. In fact, the first of their kind are already underway — one, Masdar City, in the United Arab Emirates, and the another, PlanIT Valley, is planned for northern Portugal.

Masdar City (above) is a solar powered, sustainable, zero-carbon, zero-waste city.

PlanIT Valley (below) is an experiment using 100 million sensors controlled by a central operating system.

Much of this will be made possible by a relatively simple technology called Radio-frequency Identification (RFID). RFID uses tiny chips embedded in objects that send data over radio-frequency electromagnetic fields. With technologies like RFID and cloud infrastructure, the possibilities for bringing a sense of awareness to objects is virtually endless, but I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to imagine that a sufficiently dense sensor layer would help us solve some of our most pressing problems.

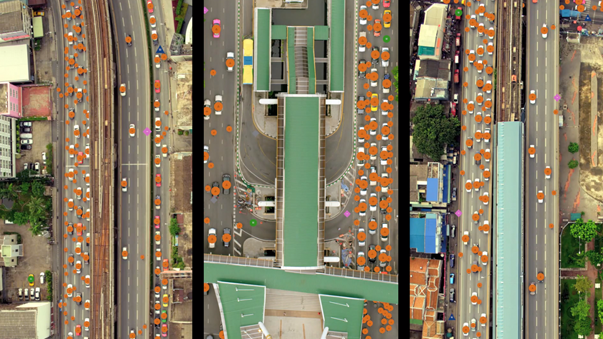

In the animation below, I’m showing — at a very, very basic level — how machines might track the various systems essential to the day-to-day workings of urban environments, like traffic, sanitation and electric systems, and even the faces of the people living there. Once those discreet items are identified, the background need not be captured at the level of detail the human eye is used to.

RFID sensor layers will help us solve the major challenges created by our technological progress.

This animation shows how a machine might see different networked physical systems, like vehicles,

sanitation, electrical, and even people (above).

This still (below) comes from a hypnotic video created by Timo Arnall titled Robot Readable World,

which explores this idea even further.

Analysis of the enormous datasets gathered by a city laced with sensors could produce significant benefits, such as more sustainable and efficient infrastructure and distribution of resources, increased safety, even job creation (someone will need to build all this stuff). Ericsson’s recent report on networked society demonstrated that a “sentient” city will reap significant financial, social and environmental rewards. One salient point from the report on the value of connectivity is that “doubling broadband speed for an economy increases GDP by 0.3% – which is the equivalent of USD $126 billion.” The finances alone will drive many cities to move in this direction. IBM has been selling this idea — quite beautifully, I might add — for years with the hopes of providing the software that cities will need to manage and measure it all.

Here’s another example from IBM that fits within the overall scope of a city’s “sentience” and its economic benefits: IBM released its own report on smarter cities that includes analysis of the economic impact of traffic — they measured it at $4 billion per year just for New York City. As for the United States overall, IBM has estimated that traffic congestion is growing at 8% per year and cost $78 billion in 2005 alone. It’s their belief that the right analytics tools and data distribution will allow cities and citizens to manage transportation more efficiently and avoid congestion altogether.

There’s a lot of excitement, understandably, about the potential of an “internet of things” and what it might make possible for cities and other communities. But there are also legitimate concerns. frog’s Jan Chipcase responded to these ideas with some important questions about what results might come from how networked city infrastructure will blur the lines between public and private. This kind of thinking also needs to be part of the conversation.

IBM’s THINK tells the story of how large-scale analytics will help solve future problems.

The goal, as I see it, is not to build a techno-utopia. A world with more machines is not necessarily a better world. Nor is it expressly to build a techno-dystopia. Instead, it’s to avoid collapse scenarios that, unless prevented, could be far worse.

On the list of problems to solve, communication has sat at the top for far too long. The other problems we face — crumbling infrastructure, a dwindling supply of natural resources, pollution — have been deprioritized. But more importantly, they’ve also out-scaled our cognitive capacity. We’re smart enough to recognize them and even to propose legitimate solutions to some of them. But we are not going to be able to solve them all before irreversible damage is incurred. Nor will we be able to see how these problems are interconnected in order to avoid proposing a solution that might nip one issue in the bud but make another worse. There’s an urgency here that is just as significant a motivator as exploring a new technology on its own merits. So, if there is any hope of a world with a healthy balance of the natural and the technological, we are going to need to increase the ubiquity of the machine in the short-term. This is where the tension lies — for me, at least — between the needs and values of humanity and the increasingly machine-friendly world we are building. There’s that human progress landscape business again. There are questions, and while the immediate future can certainly look inhospitable and perhaps even frightening, we no longer have the luxury of simply aborting contemporary technology. This might have been an option before we invented plastic 😉 But certainly not now. It may be daunting, and perhaps we’ll even find out that it’s in some ways futile, but it should also be inspiring. After all, if a livable future is possible, what could be more inspiring than working to build it?

There are, of course, costs to consider. I don’t mean financial ones, really, though those certainly are relevant. I mean sociological costs.

Design: Design and its resulting technology have been focused on the visual for so long, but this will shift. What will design mean when we’re designing the unseen? When we’re designing with sounds, textures, vibrations, smells, and temperature? This sort of thing is the future of interaction design.

Work: Many, many jobs will be needed to construct “sentient” cities, so there seems to be no shortage of employment and manufacturing opportunities in this vision. Meanwhile, the software component is moving more and more quickly toward automation that there may be a return to labor jobs while computing and analysis are left up to machines. We’ll see. But this could be a significant and potentially volatile shift (see Douglas Rushkoff’s piece asking if jobs are obsolete for another point of view on this) in work culture for western nations.

Invisible doesn’t mean hidden.

Privacy: When everything is invisible, everything is visible. Is there anything more quaint than the idea of locks, gates, walls, and curtains protecting privacy? Privacy no longer has much to do with physically keeping out prying human eyes. It now has everything to do with being mindful of what data exist about you?particularly online?and how machines can observe and interpret your activity. This is already an issue — Acxiom has 1500 items of data on 96% of Americans (so, probably you) — but it will get worse. With the amount of data we’re talking about, it’s far cheaper to keep it all than to sort it and discard the irrelevant stuff. And given how inexpensive storage is, we have the luxury of supposing that what’s irrelevant today may become relevant tomorrow. But consider how that approach will affect law enforcement. Why investigate suspicious persons when you can analyze everyone’s patterns? A recent article in Technology Review quoted John Pistole, a former deputy director of the FBI, who said, “We never know when something that seems typical may be connected to something treacherous.” That is surely a more efficient and effective means of tracking down criminals, but it also reverses an important American tradition of considering everyone innocent until proven guilty. After all, we also never know if something that seems typical is typical. Suddenly, we’ve got technologically-validated paranoia.

The legal and civil liberties issues here (here’s just one can of worms, if you’re interested) are such a mess that I’m not certain we’ll be able to sort any of it out (in a way that protects us) before it gets even worse, because the tracking we’ve become accustomed to online will follow us into the real world.

Just one example of that: Drones (of many varieties, like this, this, this, this, this, and this). Drones are useful for doing all kinds of work remotely — anything from maintenance to scientific reconnaissance to surveillance to warfare to asteroid mining. In general, drones, like any other technology, are not moral agents, but they’ll be used by people and for purposes of varying moral character. They’re not necessarily to be feared, though they could be. You think it’s startling to have a silent Prius sneak up behind you on the street? Try a tiny, silent, agile-flying drone with cameras and microphones attached? Or fifty of them. Drones could potentially be in the sky, on the ground, and all places in between. There will have to be codes and permits for that sort of thing, of course. Thinking more long-term — and contrary to the image below — they probably won’t all be visible. If they’re anything like these, I’d rather not know they’re lurking, anyway. Oh, and once they are everywhere, we’ll probably spend lots of time figuring out ways of deceiving them, especially if they’re there to keep track of us.

Expect drone swarms, but don’t necessarily expect to see them…

…and we all should hope that they’re not the retina-scanning spiderdrones of Minority Report.

Data Security: Plenty of companies today are selling single-sign on systems (to universities, hospitals, law firms, etc.) that offer significant value in terms of procedural efficiency gains. If a doctor, for example, can sign in system-wide once using a biometric of some kind (fingerprint or retinal scan, for example), she might save a significant amount of time in the aggregate — time she can instead spend treating patients. But this also means that a third party now has access to a significant amount of the hospital’s data. With enough customers, a third party single-sign on software company could be vulnerable to hackers, putting a tremendous amount of patient data at risk. For this, there are solutions, of course — things like firewalls and encryption. But the point is that as the complexity of our data collection and analysis practices grows, the need for security and privacy measures compounds. No system will ever be 100% secure.

Additionally, there are legal compliance issues to navigate that pertain to patient information confidentiality and security requirements for technological systems that interact with that information. Instead of developers being expected to gain expertise in things like HIPAA compliance (familiarity, yes; expertise, no) those involved in healthcare of any kind should grow in their understanding of technological issues. Each side needs to bring awareness and a point of view to the table and cooperate in order to ensure the best result. I only mention this because I’ve observed the opposite.

Aside from high-level security and legal issues, we should be asking ourselves these questions about the collection and analytic practices we’re involved in: What can be done with the data? What can be known about you based upon where you go in the online world and the real world? What do you want to be known about you?

Human progress will always provoke questions of what it means to be human.

Free Will: In IBM’s THINK presentation, the narrator describes how sensor layers embedded in city roads are already helping to build databases of information related to road use and traffic patterns:

“What if we saw traffic as data? … This data can be organized into dynamic maps that reveal a system-wide view of causes and effects. And models can help us understand why traffic forms in the first place, and predict how it will evolve.”

This method has obvious implications for city planning, like knowing how and where to build roads, the best mechanisms for controlling and directing traffic, refining way finding, etc. But the implications are intriguing, especially as they relate to prediction. The subtext here is that with enough data, IBM’s analytic tools could also predict traffic patterns. The subtext of that, of course, is that IBM’s analytic tools could also predict driver behavior. Plenty of research is being done on that front — some studying computational models of driver behavior and others the ability to predict driver behavior based upon facial-expression analysis.

The leap from predicting traffic patterns to predicting individual driver behavior is a big one, and certainly a profound one. Traffic is a system, composed of many factors — such as location, time, weather, size of road, speed limit, local driver demographics, etc. — which can also be systematically analyzed. That’s not shocking. By taking into account that sort of thing, predicting when a stretch of I-95 in Baltimore is likely to be congested seems feasible. But when you consider the individual choices of drivers — when they speed up, slow down, cut someone off, change lanes, become distracted, answer a phone call, etc. — the complexity of what creates congestion increases significantly and seems almost impossible to really predict. But, if enough data is collected, trends, even on the micro scale, are likely to emerge. What does this mean? From this vantage point, it seems our decision-making may not be as unique as we think.

My guess is that once we start becoming more aware of the predictive capabilities of modeling tools with super-sets of data behind them, we’ll become more nervous about them and what they reveal about the control we believe we have. The more predictable our behavior is, the more we’ll question our individuality, if not our free will.

It’s worth pointing out that in the film Contagion, which I briefly mentioned earlier, every bit of information the Center for Disease Control was able to access and analyze in their effort to track down and control an outbreak of disease was gathered as a result of the characters’ willing forfeiture of privacy — by using cellphones, the internet, being in public places, and using public transportation. Just like we do. We are already building this superset of data, which includes so much more than the results of our decisions. It also contains our preferences. As that information merges with the datasets that IBM imagines, what could be known and/or predicted about us could be quite troubling, not just from a privacy standpoint, but an existential one.

This kind of philosophical question is beyond the scope of this post, but I want to leave it with you to think over. Technology is also like a mirror, and if it begins to reflect back to us something that we don’t recognize, we must determine why and what, if anything, we can do about it. We need to be comfortable pushing any technological discourse — no matter how low-level, like the apps-vs-web debate — into this territory in order to ensure that we never lose sight of the big picture, which is ultimately a balance between two questions: What kind of a world do we want to live in? and What kind of a world do we live in?

To design is to think of our future.

Why should any of this matter to designers? I think every aspect of technology is related directly to design. Technology, after all, is the product of design in its most basic sense. But to answer the question, I will leave you with a passage I wrote to conclude one of my Print magazine columns from last fall about the future of interaction design:

“Design has always been about possibilities, not hard-and-fast definitions. That’s important to remember as technology pushes the boundaries of professional identities and challenges the distinctions among designer, engineer, and technologist. But technology is more than just a tool; it’s an expression of intent. It is how we shape the world around us and conform it to a vision of how we want to live. In considering our futures, we must question how technology will define who we are and what we do. Should technology determine what it means to be a designer, or should the progress of technology be designed? I believe that we’ll find the answers to these questions, but not without participating today in the project of imagining the world we will inhabit tomorrow.”

Hope this got you thinking…

P.S. All of this info and I didn’t even mention Google Glasses or 3D printing.